By Saleyne Mahamat Djarma

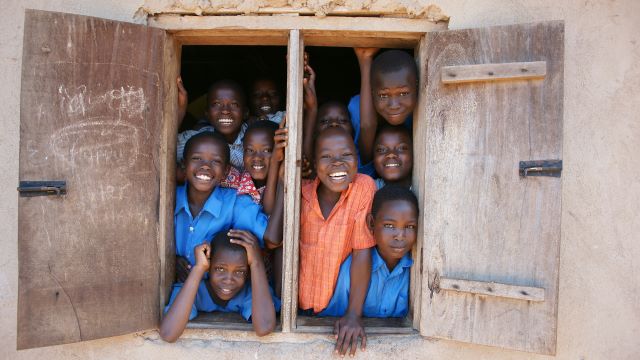

MANDJAFAR, CHAD — In the quiet village of Mandjafar, tucked along the dusty plains of southern Chad, a group of children gathers each morning beneath a simple straw-roofed structure. There are no glass windows or digital whiteboards—but the energy inside is electric. For these students, many of whom are the first in their families to attend school, learning to read and write is more than education; it’s liberation.

“Before, we had no school here,” says Mahamat Youssouf, a local farmer and parent. “Now my daughter can read signs, help with the market, and even teach her younger brother the alphabet.”

Over the past five years, grassroots efforts supported by local communities, NGOs, and international partners have been quietly transforming rural education in Chad—a country where more than 75% of the population lives outside major cities and where access to formal schooling has long been a challenge.

Community at the Core

Much of this change has come from the bottom up. Village education committees, known locally as Comités de Gestion des Écoles, have played a critical role in identifying needs, recruiting volunteer teachers, and building classroom spaces with local materials.

One such initiative is the Education Cannot Wait (ECW) fund, which has helped construct temporary learning spaces in rural areas and provide learning materials to underserved communities. According to UNICEF Chad, more than 200,000 children in remote regions have benefited from these community-led efforts since 2021.

“We don’t wait for government trucks to bring chalk,” says Maimouna Adam, a committee member in the village of Béré. “We make blackboards from wood and buy supplies together.”

Literacy Gains Among Girls

Perhaps most inspiring is the growing participation of girls. Thanks to the efforts of organizations like FAWE Chad, local leaders are working to shift cultural attitudes and remove barriers such as early marriage, domestic responsibilities, and long travel distances to school.

“Just a few years ago, many families didn’t send their daughters,” says Aché Toupta, a primary teacher in Tandjilé region. “Now, some of my brightest students are girls.”

A partnership between UNESCO and the Chadian Ministry of Education has expanded mother-tongue literacy programs and provided scholarships for rural girls entering secondary school.

Training the Next Generation of Teachers

To sustain these gains, the country is investing in its own educators. At the Teacher Training Institute in Sarh, young men and women are being trained not only in pedagogy but also in trauma-informed practices—vital in a country where conflict and displacement have left many children vulnerable.

“In the past, some teachers were barely older than their students,” says Hamidou Idriss, a program director. “Now, we are seeing a new generation of trained, passionate teachers returning to serve their home villages.”

According to a World Bank report on Chad’s education sector, the teacher-to-student ratio in rural areas is gradually improving, and early-grade reading proficiency is on the rise.

Local Innovation

Technology may be limited in remote parts of Chad, but innovation thrives. Solar-powered radios are now used to broadcast literacy lessons in areas without electricity, and mobile libraries—sometimes delivered by donkey cart—bring books to villages that lack traditional schools.

An app developed by local youth through the TechnoServe Chad initiative allows parents to track their children’s attendance and access health and education alerts. “It’s small steps, but they add up,” says Amina Malloum, one of the developers.

The Road Ahead

Challenges remain: teacher shortages, seasonal dropouts due to farming obligations, and funding gaps continue to affect learning outcomes. But optimism runs high.

“We still have work to do,” says Maimouna Adam, glancing at her blackboard scribbled with chalk. “But we’ve shown that change is possible—even without much money, even far from the city. We believe in our children’s future.”

As Chad pushes toward its national goal of universal primary education by 2030, the determination of its rural communities may prove to be its greatest strength.